Curious caregiving

This post is about caregiving for adults, as that’s what I’ve been doing the past few weeks. Figured a lot of readers have similar responsibilities. The ideas are relevant to grandchild care, but if you’re looking for grandchild specifics, head to a different post!

A friend asked whether she should buy a parrot.* I tried hard to convince her not to. This person, about my age, lives in an apartment. I told her what I knew about problems with parrots—noise, mess, and more noise. The fact that the parrot is likely to long outlive her. The time required to keep it stimulated and entertained. The difficulty of leaving it if you want to vacation. The fact that all this becomes someone else’s problem—the noise for your neighbors, the care of the bird when you become ill or die. She bought the parrot anyway.

The predicted problems ensued: The bird’s squawking infuriated the neighbors, the apartment was full of down and bird poop, and my friend needed to turn down a vacation because of parrot care. In fact, her leaving the bird at all was a problem, because it made even more noise when it was lonely. But the parrot filled her days, whether with the joys of communicating with it or the worries and tasks of managing it.

Who knows best?

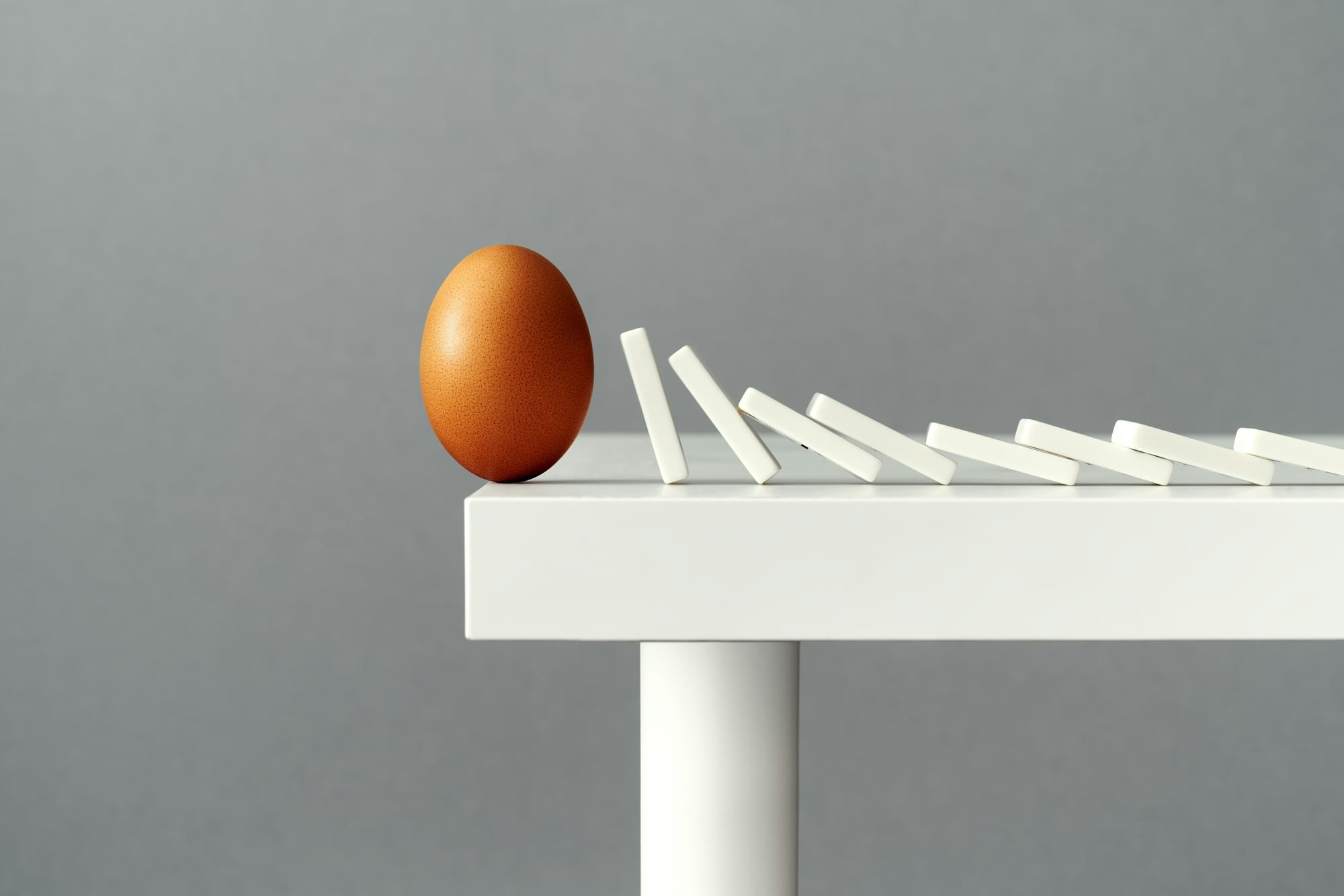

Once you begin advising or caring for another person, it’s easy to get attached to the notion that you know best, and to become irritated or resentful if the person obstructs your agenda—carefully thought out, as you believe, to be in their best interest. That is classic paternalism. I, advising my friend, deem that she has made a bad mistake. How can it be good to alienate your neighbors, live in a mess, and limit your own opportunities for getting out? But my friend sees it differently. The parrot has become her world, and she is OK with that: social alienation, mess, practical limitations, and all.

Setting aside the needs of the neighbors and the bird, let’s look at my paternalism. It has a couple aspects, knowledge and control. I knew what would happen—parrots make notoriously difficult pets. And, once my friend asked my advice, I assumed she would take it: There’s the control aspect. Even at my age, it’s a bit of a shock to have my knowledge rejected (for unclear reasons, at that!) and to lack control.

Just past that initial shock, though, I’m aware that having control over events—or even of myself—is to a great extent an illusion. For example, my ability to “control” my health is largely related to my genetics, plus the good luck to grow up in a healthy and active environment. To the extent I have ever controlled others—children, staff at work, students—their “compliance” has largely been directed by their own motivations, or by the system in which we find ourselves. The extent of my knowledge is similarly illusory: In fact, there are very narrow slices where I know unequivocally right answers (such as addition, crossword puzzle answers, and traffic laws), and vast areas where the information I hold is tentative (because no one knows), where I tentatively hold information (because I’m not sure), or I am clueless (for example, anything about the future [thank you, David Hume]). Importantly, no matter how hard I try, I don’t know what it’s like to be my friend in the mess of poop and feathers—I can only imagine what it would be like for me (thank you, Thomas Nagel).

So my friend buys the parrot, and I am stewing about it. Then I read these words, from On Giving Up, by Adam Phillips: “…knowledge, the will to knowledge, can itself be a defence against curiosity…” (p. 108). Indeed, “…knowledge can be the death of curiosity.” (p. 112) And I realize that the thought would work equally well (for my purposes), altered to, “Control, the will to control, can itself be a defense against curiosity; indeed, control can be the death of curiosity.” Not only do I not have control over someone else’s decision, not only do I not have knowledge of her experience or of the future, but in addition, by assuming I have knowledge or control, I am actively closing off the possibility being curious about my friend’s concerns and my own reactions. I cut off the possibility of seeing more, learning more, considering alternatives, and growing. I can ask: How does she feel about the parrot? What is her life like with it and without it? What alternatives are available for good parrot care? Why am I so dead-set against raising parrots? Why do I care about being right?

But she's making a mistake!

But wait, I care about my friend, and—vagaries or no—I can see that she has made a bad decision: She is busy, but not happy. Not to mention the perspectives of the neighbors, and, eventually, the bird. Should I get more insistent about her giving up the parrot? Work with the neighbors to have management kick it out? We’re at a central question about paternalism: What are the limits are on letting people make their own decisions? Medically and legally—but often very uncomfortably for those of us who care about individuals—people are allowed to make harmful choices for the sake of preserving their freedom. For example, people are allowed to drink themselves to death; they can be jailed or hospitalized for a few days to detox, but unless they have committed a crime, there’s nothing to stop their buying the next bottle when they get out. Practically speaking, too, control of another person’s life—short of frank coercion—is even less possible than control of one’s own.

Obviously, my friend’s giving her time and life over to a parrot is less extreme than drinking herself to death. In this hypothethical, relatively uncomplicated situation, I could simply wash my hands of it. In real-life scenarios, walking away might or might not be the right thing to do. Paternalism is clearly appropriate in the situations where medicine and law allow it—when the person you are acting for simply cannot make decisions. On the other extreme, it’s clearly inappropriate when the advisee is fully competent and purposefully disagreeing with your agenda.

But many situations—including my friend’s, in real life—are in a wide gray zone. The person you are advising might agree with you, but have a block or habit or objection that gets in the way of taking your advice. They might agree with you, but be unable to follow the advice for physical, emotional, or cognitive reasons. And they might disagree with you for reasons that you’re having trouble discerning. I’m finding that it’s especially in that wide gray zone where it helps to get curious about why the person is not following your lead. Exploration might lead to ways to get to the same endpoint (get rid of that parrot!), or to alternatives (such as ways to better care for the parrot). I’m also committed to giving up dreams of knowledge and control for a dose of humility, working to recognize my own limitations.

Replacing paternalism with curiosity and humility is not going to erase the tensions of caregiving or its refractory case-by-case, moment-by-moment concerns. But it can’t hurt.

*I’ve changed a true story to protect a person’s privacy.